Kashmir Scholars Consultative and Action Network Stop Arrests of Human Rights Defenders in Kashmir Public…

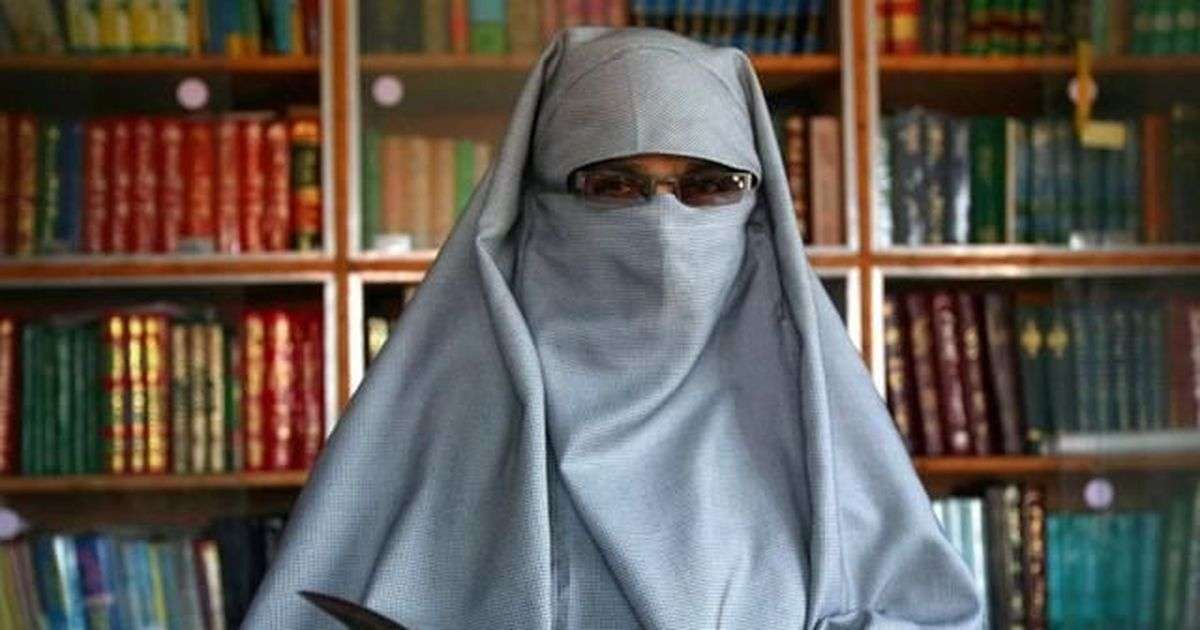

The case of Female Political Prisoner Asiya Andrabi

Kashmiri Prisoners of Conscience:

Introduction

- Asiya Andrabi, 62, a scholar and teacher of Islam, a prominent pro-freedom Kashmiri resistance leader, and the wife of Kashmir’s longest-serving political prisoner, is currently serving out the 12th year of her detention.

- Andrabi has been slapped with the draconian Public Safety Act more than 20 times throughout her life, and has been under detention at Tihar Jail, New Delhi, since 2018, booked under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

- She is the chairperson of Dukhtaran-e-Millat, the largest all-women socio-political and religious organization that advocates for Kashmir’s liberation from Indian colonization, organizes Ḥalaqahs throughout Kashmir to disseminate knowledge of Islamic sciences among women, oversees economic rehabilitation centers for widows and orphans of those murdered by the Indian state, and works actively against India’s exploitation of Kashmiri women.

- She is the wife of one of Kashmir’s longest serving political prisoners, Dr. Muhammad Qasim, a scholar and pro-freedom leader, who has been behind bars for over 29 years now.

Background: Her Ideas and Politics

- Born in 1961, she graduated in Biochemistry from Women’s College, then completed her post-graduation in Arabic and Islamic Studies from University of Kashmir.

- In 1983, she witnessed an army raid inside her college premises. It was a bid to control growing student protests, and students were dragged out of their classrooms and hostel rooms and beaten mercilessly, including women students. The treatment meted out to the students of her college by the forces of occupation agitated Asiya. She climbed up to a pedestal and while addressing her fellow students questioned the army’s high-handedness inside educational spaces. Thousands of students gathered around her, echoed her sentiments, and raised slogans in favor of liberation and Islam and against the human rights violations. In the charged atmosphere, she led the protesting students out of the college to the central city square where more civilians joined her, emboldening her voice.

- In her 20s, as Asiya gained a reputation of her own in religious circles due to her pursuit of knowledge, a Ḥalaqah in her neighborhood asked her to teach the Quran to children. When she arrived to teach her class, she was overwhelmed by the fact that most of the mothers of these children knew very little about Islam and the rights and responsibilities that it gives them as women. She decided to dedicate herself to educating women through Ḥalaqahs. She started the first women’s Ḥalaqah in the year 1985, which aimed solely at granting women religious training.

- In 1985, the Ministry of Culture, New Delhi, flew a troupe of Kashmiri female dancers to Delhi, to perform in a cultural program. These dancers, from poorer sections of society, were compelled to take up this work. Asiya and her women contemplated the situation of the dancers and organized a full-fledged movement against it. They discussed women’s exploitation and their sexualized use only for amusement in Indian government circles. Asiya drafted her first pamphlet, ‘A Message to the Daughters of Fatima’, and distributed it among young women in various places in Srinagar. Questioning the state’s role in the exploitation of women, Fatima Zahra, the daughter of the Prophet Mohamad, was presented as an alternative symbol of piety and womanhood as against Bollywood’s construction of women. The Kashmiri community applauded Asiya and her comrades for their work on the issue. The daily Aftab, a local newspaper, called them ‘Dukhtaran-e-Millat’ (Daughters of the Nation), a name that they happily adopted. The single Ḥalaqah branched out in every district of the Kashmir valley—women from the middle and lower classes became part of the movement. Dokhtaran organized a media cell, and Asiya’s lectures were recorded and made available as CDs and cassettes in the local market for wider consumption.

- In 1985-1986, Asiya took the movement further by making certain demands to the government; the first was a demand for separate, reserved seats for women in public transport as they suffered daily due to men overcrowding the buses. Asiya who did not believe that anything could be gained by meeting ‘corrupt, pro-India politicians’ even decided to meet the then chief minister Farooq Abdullah along with fifty other women and impressed upon him the need for separate buses for women but he rejected their demand and mocked it, saying that we were living in the 20th century and Asiya, with this demand, was trying to take a regressive step which would take Kashmir back to 1400 years ago. To this, Asiya responded that as far as she was concerned, it would be best for humanity to return to the just Prophetic values of that era.

- Asiya was 25 years old in 1987 when the elections were held in Jammu and Kashmir. She believed strongly that the movement for liberation couldn’t be sustained through the process of sham elections and that it was a political blunder and a moral contradiction to want liberation from India on the one hand and swear by the Indian constitution, on the other. She believed that the solution to the Kashmir issue cannot emerge from within the Indian apparatus and instead requires an international intervention. Asiya supported the armed resistance against the occupation and considered it a legitimate right of the oppressed people to resist oppression by any means necessary.

Government’s Crackdown, Family, and Detentions

- It was in 1990 that the government officially banned her organization, forcing Asiya to go underground as her house was raided almost every other day. It was around this time that Asiya got married. Her condition was simple: her husband should be a pro-freedom activist and a practicing Muslim, and so she married Dr. Muhammad Qasim, a freedom fighter and a scholar. Her elder son Mohammed was born on June 13, 1992. When Mohammed was seven months old Andrabi and her husband along with the baby were arrested at the Srinagar Airport on their return from New Delhi. This is when the family of three was separated for the first time.

- When arrested for the first time, Mohammed was isolated from his mother for a year. Such was the effect on the child that his mother says he would bang the door with a stone the entire day. “That stone was his toy.” For the first two and a half months, Asiya and her husband were interrogated every day. Dr. Qasim was subjected to torture in front of his wife.

- Qasim was released in December 1999 and their second son Ahmed was born at the same time while they were still hiding from the government. He was held again in the same month and remains in jail. He has been sentenced to life imprisonment. The couple has been married for three decades but has spent less than 3 years together, and that too in hideouts. Her husband has been in prison for 29 years now.

- When the ‘sex scandal’ surfaced in Jammu and Kashmir in 2005-2006, Asiya played a leading role in exposing the nexus that she believed existed between the army, the bureaucracy, and the politicians. While demanding a thorough investigation and punishment for the ‘culprits and the accused’ she simultaneously raided many houses that were running the sex rings. She was arrested under the Public Safety Act during this period for ‘taking the law into her own hands’ but later released due to intense public political protests and outrage against her arrest. The victims of the scandal themselves had chosen to turn to Asiya instead of the police due to their usual complicity in such scandals. Asiya was also jailed for opening rehabilitation centers and organizing financial support for the widows and orphans of the martyrs of the cause and booked under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA).

- Asiya faced monthly arrests from 2007 to 2009. During the unrest of 2010, she was held for two consecutive years, as she was instrumental in organizing protests against the military-occupation. The year 2009 was very difficult for her as she was jailed in Jammu and her barrack was turned into a Mandir (Temple) by fellow inmates to psychologically torment her. She was jailed that year for mobilizing women against the rape of two Kashmiri women by occupation forces. She suffered severe lung disease due to the smoke of the incense during imprisonment and tear-gas during protests, as she is a patient with acute asthma and multiple respiratory ailments. Asiya played a pivotal role in organizing anti-occupation protests in 2016, after the killing of Burhan Wani.

- In 2019, Andrabi’s house was also seized by the Indian government, under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

Imprisonment Away From Home and Treatment in Prison

- As Asiya is in a jail miles away from her home, her family rarely is able to visit her. She is allowed to call home only once in a month, for a few minutes. When relatives meet her, they are subjected to rigorous frisking and humiliation in order to mentally torture Asiya.

- Asiya’s husband is also in a different jail and the couple have not seen or met each other for the last 5 years. Despite the court order allowing the two to have a brief monthly call, jail authorities often flout the order and deny them this right.

- During her calls with her family members, she is not allowed to sit on a chair despite having acute back pain. Rs. 500 is fined if she sits on a chair.

- Despite being a patient of Diabetes, Asiya is only given potatoes and starchy foods as a diet, worsening her health. She is denied proper medication for her ailments and also denied needful fruits.

- Asiya petitioned court demanding that she be allowed to possess books. Instead, the presiding judge in the court chided her for her request and told her to read her long charge-sheet instead.

- Despite Tihar Jail being extremely overcrowded and Asiya having multiple ailments that make her particularly susceptible to Covid-19, she has been denied any relief.

The Scope of International Law

- Article 15(1) of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 11 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) enshrine the principle of “legal certainty,” which declares that the criminal law must clearly lay out what constitutes an offense so as to avoid any arbitrary application or abuse of the law. In contrast, UAPA, under which Asiya Andrabi has been detained, offers a very loose and vague definition of what constitutes a “terrorist act”, making abuse of law easier. It is important to note that the definition also includes any act that is “likely to threaten” public order, giving the government unrestrained power to jail a person who has not even committed a crime yet.

- As a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, India is bound to ensure the right to liberty and security, which also includes the right not to be detained arbitrarily, and to be informed of charges and the grounds for detention. It also includes the right to be presented in front of a judge within a small period of time following the arrest, and to appeal to a court of law to review the case. As a result, the Human Rights Committee says that the Act violates the rights enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, especially the rights to liberty and to a free and fair trial. Andrabi has been booked under PSA more than 20 times.

- According to the United Nations OHCHR guidelines on political prisoners, all prisoners shall be treated with respect due to their inherent dignity and value as human beings. There shall be no discrimination on the grounds of race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Andrabi has for long been subjected to denial of religious rights in prison, like the right to pray.

- The detention of Andrabi, and the denial of rights in detention, also violates European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.