Justice For All Statement on Torture and Extrajudicial Killings in Kashmir February 18, 2025 Justice…

From the Valley to the Holy Land: The Legacy of Kashmiri Hajj

By Staff Writer

I was born and raised in the Himalayan valley of Kashmir. Kashmir is known for many different things: the scenic beauty, the unending occupation, and its Islamicate culture.

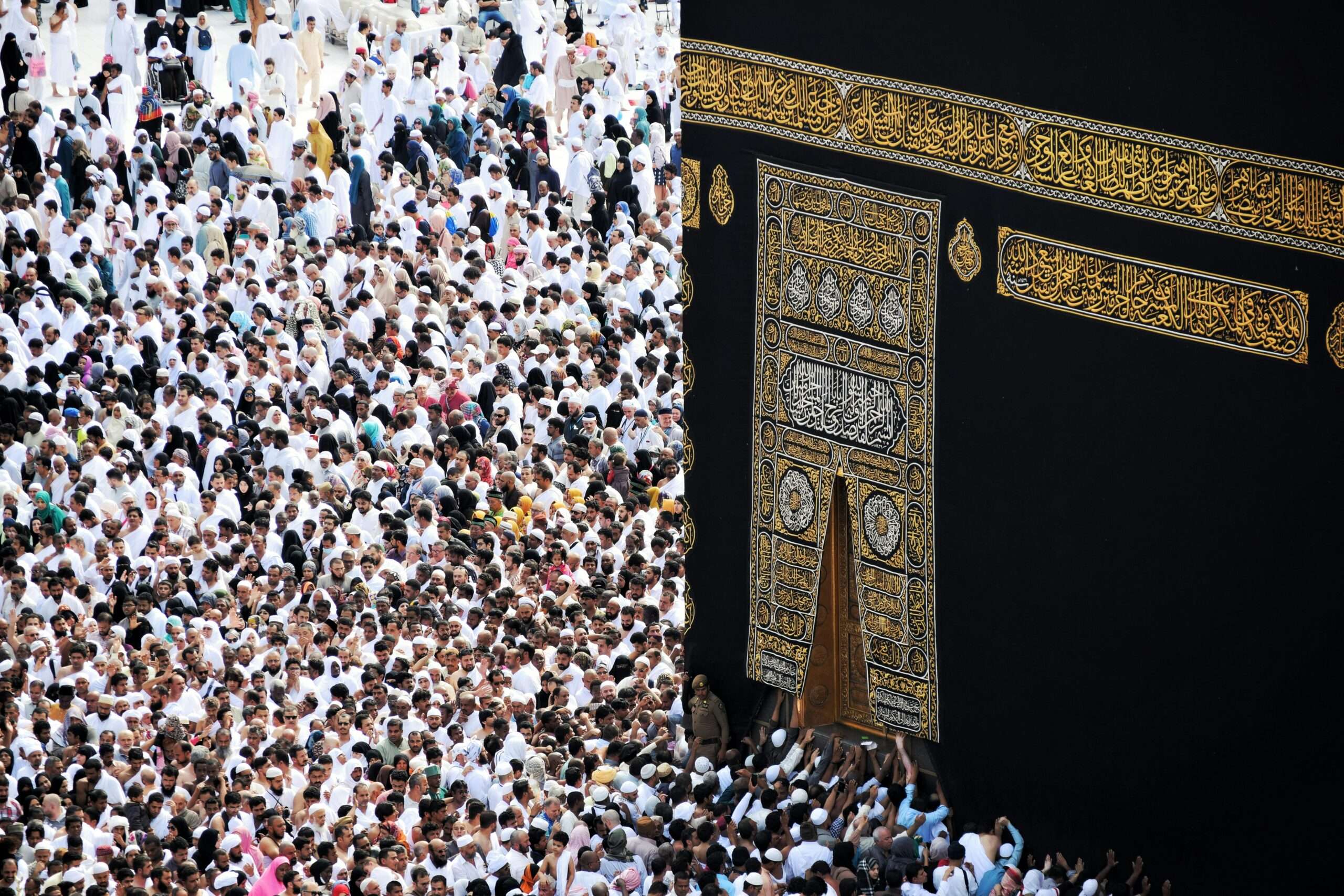

But the story that I am writing about is the journey of Hajj, a journey that I heard many stories about from my Boba (grandmother) during my childhood. As one of the five pillars of Islam, Hajj has a central place in the religious life of our Kashmiri Muslim community and it is not just a matter of individual worship, but it has a social and communal value. Those who perform Hajj, known as Haej, receive respect and honor from kids and old alike. They are turned to for advice at the time of disputes and when a Haej comes to offer prayer in a mosque, a place is made for him in the first row.

I asked my Boba about how Hajj was for people of Kashmir before the advent of modernization. She told me that the journey to the beloved cities of Mecca and Madinah was very difficult and because poverty was very widespread in the valley, only a few people would make the journey. It began as a long road journey to Bombay or Karachi, and then sailing to Jeddah. Then the pilgrims would either walk or climb a camel’s back and head towards Kaaba. Boba used to tell me that Hajj is not the same anymore, as the journey that once took weeks or months is now accomplished in some hours. She told me that Hajj in old times was very painstaking, but Allah must have loved the people who performed it because of the pain and difficulty they endured. And that only sincere and devoted people would make the journey as it was both physically and financially challenging. The point that she was trying to make was that in today’s times, the ease with which Hajj is carried out may diminish its spiritual value in the eyes of Allah, as it no longer entails similar sacrifice or toil for many people.

Khalid Bashir, a Kashmiri scholar, in his book called Kashmir: Looking Back in Time walks us through the stories of Kashmiri performers of Hajj from the past.

One such man was Abdur Rehman who performed Hajj in the 1930s. He had traveled on foot through Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq, to reach Mecca. Then he remained in Madinah for around 10 years and worked as a sweeper there. In 1948, he returned to Kashmir and people greeted him with great love and asked him to make prayers for them. He was also made the Imam of a mosque, on account of his piety (taqwa) and love of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him). Many people thought that Abdul Rehman had passed away, because a pilgrim who did not come back in one or two years was presumed dead, and the family would offer such a person’s funeral in absentia, known as ghaibana namaz-e-janaza. Boba told me that her husband, my Naana (grandfather), took part in at least two such funerals in his teenage years. A man named Muhammad Rajjab of Srinagar had left for the journey of Hajj, and for years, he did not return. When he finally did, his family was so pleasantly surprised.

Khalid Bashir writes that many Kashmiris who went for Hajj preferred to settle down in the holy land. He quotes Nawab Mustafa Khan Shaifta, Urdu poet and a contemporary of Mirza Ghalib, who left for Hajj in March 1839, mentioning Kashmiris as one of the communities of “different countries who have settled down in Makkah.”

Mustafa, my friend’s grandfather, is himself a Haej. He made the sea voyage to Hajj, and I asked him about the details of the journey. He told me that during the voyage, he was provided with food on board, as cooking was not allowed at all. The travelers were provided with tea after Fajr-prayer, breakfast, lunch, tea after Asr-prayer, and dinner. Mustafa told me that he, along with other deck passengers, had to choose between some dishes. The passengers of first and second class did not have to make such a choice and could eat from all the dishes available. According to Mustafa, all cooks, staff-members, and attendants employed on the ship were Muslims. All the passengers had to carry their own utensils in which food was to be provided. Khalid Bashir mentions in his book that there were ‘No waste taps’, from which one could take water only four times in a day, with a two-hour gap. Mustafa told me that the journey was difficult for many Kashmiri Muslims because Kashmir has a very cold climate, as it is a mountainous region. The strong heat of Arabia and the sea-voyage would leave many Kashmiris sick and nauseated throughout the journey. But illness was said to have erased the Gunaah (sins), so it was viewed as a source of spiritual purification.

For many years, sea voyage was the primary mode of Hajj journey not just for Kashmiri Muslims, but for South-Asian Muslims in general. The departing points for these pilgrims were Karachi and Kolkata, then known as Calcutta. Mumbai point, then known as Bombay, was added afterwards. Pilgrims from the valley of Kashmir would mostly take the Karachi route. Mustafa took the same route to Karachi and traveled through parts of Punjab that constitute Pakistan today. He told me that this plan of journey was common until 1947, when the decolonization of British India happened into India and Pakistan. The distance between Srinagar and Karachi was around 600 km less than the distance between Srinagar and Bombay. Karachi was also closer to Jeddah in comparison to Bombay. Hence it was the preferable route. Khalid Bashir mentions that the “pilgrims carried no passports and their travel document was a Pilgrim Pass issued by the concerned Deputy Commissioner or by the Port Haj Committee against a payment of 8 rupees, if the pilgrim failed to bring it from hometown.” After the year 1947, Haj pilgrims traveled in buses from Srinagar to Pathankot, a distance of 427 kms. From there, they would hop on a train to Bombay and then sail to Jeddah.

While the valley of Kashmir is thousands of miles away from the holy cities of Mecca and Madinah, in the year 1950s and onwards, many muallims from Saudi Arabia would come to Kashmir. A muallim was a Saudi citizen who owned residential property in the two holy cities and offered it on rent to those performing Hajj, along with provision for food and basic facilities. The muallim would also act as the guide for the Hajjis. Khalid Bashir writes about one such muallim who was known in the valley as Zainul Aabideen. He had become popular in Kashmir and would arrive ahead of the Hajj time and register the possible pilgrims. To enable publicity, he distributed leaflets at important Aastaans (shrines) and mosques.

The number of female Haej was few until some decades back. Boba told me that this number, among other reasons, was less because women in earlier times would feel discomforted by having to submit their photographs for a Hajj permit or passport. Khalid Bashir writes that in the 1930s, a man named Amir Gul, from a district in the valley of Kashmir called Islamabad wrote an application to the governor of Kashmir requesting a passport for his mother, Gul Bibi. In the application, he wrote that his mother was very eager to make the journey of Hajj and all she needed was the passport. In the response to the application, Amir Gul was asked to submit his mother’s photograph, for the sake of the documentation. In response, he told the governor that his mother was a pardah nisheen aurat (a woman who observes Islamic veil). He told the governor that taking a photograph of a woman was not approved of in his family and therefore he cannot submit her photograph.

The time of departure and moment of return of the Haej used to be, and still is to this date, an occasion of festivity and celebration in the valley of Kashmir. At the time of leaving, pilgrims are taken in processions from their homes to the site of departure. Some young men pick the pilgrim on their shoulders. Energetic kids in large numbers join these processions and raise and respond to religious slogans. It is the responsibility of the women folk and children of the family and also the neighborhood to shower candies, almonds, and flowers on the pilgrims. At the time of the return of pilgrims, welcome charts are made by kids, and erected, and a large feast is also held by the family of the pilgrim for close and distant relatives and neighbors. At the time of leaving, only immediate relatives are invited by the pilgrim to his house for lavish meals.

Boba told me that in old times, pilgrims would carry along with them things such as Tumul (rice), dried vegetables, marchawangan and masaal’e (spices), turmeric powder, Noon (salt), green tea leaves and Kashmiri Aachaar (pickle) so that they can consume their homely food while being in a foreign land. The pilgrims carried light bedding and a large steel trunk filled with clothes. But the main purpose of the steel trunk was to carry gifts for the loved ones. These gifts generally include Khazer (dates), Tasbeeh (beads for remembering God), Jaa-e-Namaaz (praying rugs). But the most valuable gift in the eyes of the people remains the chunks of dry soil of Madinah. This gift is reserved for special family members or friends. The soil is believed to have curing properties and according to Boba, it is also considered to be a source of Barkat (blessings). Other gifts include Itr (perfume), wrist watches, Surme (kohl). Boba told me that when she was in her twenties, she was given a tape recorder by one of her uncles and a video cassette recorder by another relative. Khalid Bashir writes that while pilgrims today can only carry five liters of Zamzam, there was no such restriction in carrying Zamzam water and Kashmiri pilgrims would bring home large quantities of the water that is deemed very holy. On the return of a pilgrim, Zamzam was distributed among almost all the people forming his contact circle.

Communication methods were not as developed that time as they are today. Therefore, a Kashmiri pilgrim would remain in contact with his family only through letters. These letters usually took weeks or even months to reach their destination. While in today’s times, a pilgrim narrates and even shows, through video-call, his journey to his family members, pilgrims back then would virtually go out of communication for months. Mustafa, my friend’s grandfather, said that while it was difficult for pilgrims (to not have any knowledge about the well-being of their family members), this seclusion allowed them to worship Allah properly while forgetting about Dunia (worldly affairs).

A funny and ironic incident was narrated by Khalid Bashir in his book. In the 1970s, Dost Mohammad, an educated pilgrim from Uri, a town in Kashmir, sent a telegram to his family members from the Bombay port after a long delay. The telegram read, “Sailing today.” However, unfortunately, the telegram received by the family read “Ailing today”. The news became a cause of great anxiety for his family members, who then immediately sent another family member to Bombay to take care of Dost Muhammad. When the family member reached Bombay port, he was told that Dost Mohammad was healthy and like other pilgrims, had already departed for Jeddah.

Boba told me that in her young days and to a lesser extent, even today, it is mostly the old and aged people who would undertake the journey of Hajj. Many people only think of performing the rites of Hajj when they finish building a house and settle and marry their children off. It was then that his family members would suggest that they should do Hajj. According to Khalid Bashir, many of these old people had never traveled out of the Kashmir valley and were frightened by the idea of sea or nowadays, air travel. However, not all old people had to be persuaded to go for Hajj. But as Bashir remarks, many would delay going on Hajj to old age because they would desperately wish to die and be buried in the holy land of Mecca or more preferably, Madinah. A pilgrim from a Mohalla (neighborhood) next to ours, passed away in Madinah and he was considered very blessed and lucky by all the people.

When a Haej would return from the journey of Hajj, he would narrate to the people his spiritual anecdotes and emotional experiences. People would always eagerly listen to these stories. Khalid Bashir writes about a man named Ghulam Nabi Bhat, who performed Hajj in the early 1960s, narrating his journey of Hajj at a Naaed Waan (local barber shop). When Ghulam Nabi had returned from Hajj, his neighbors had been astonished to find that his feet were in a really bad shape with cracks in his heels and wounded ankles. When he was asked about the reason for this, Bhat told them that when he reached Jeddah, he threw away his slippers and chose to walk barefoot through the streets of Mecca and Madinah. Many people would be in tears, at the barber shop once his narration would end. In some cases, “Haeji” becomes the surname of a person and even his family members after one’s return from Hajj.