As the world celebrates International Women’s Day, many Kashmiri Muslim women languish in Indian prisons…

The obstacle in the path of justice is India itself

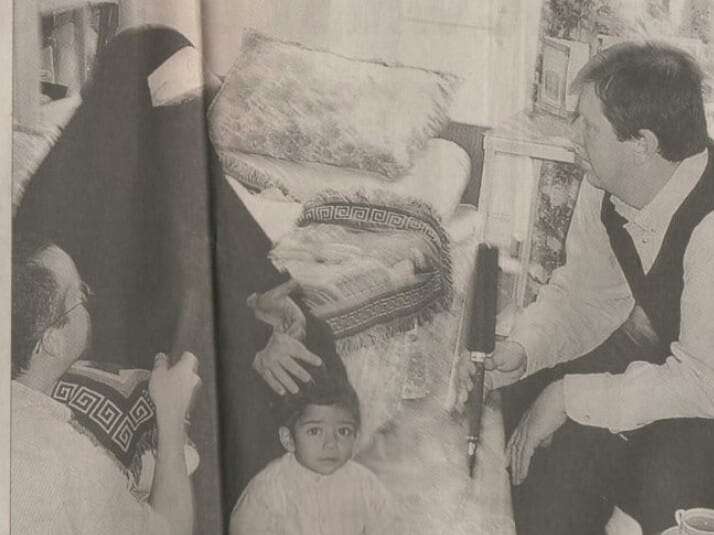

Umer Beigh in conversation with Asiya Andrabi’s youngest son Ahmed Bin Qasim, first published here in 2018

On July 10, the National Investigation Agency (NIA) attached the house of incarcerated 56-year-old Asiya Andrabi, a senior pro-freedom leader heading Dukhtaraan-e-Millat under the provisions of Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Though “no searches were conducted” but investigators maintained the property was being used for “the furtherance of the terror activities of the proscribed terror organization”. A message was further pasted on the house’s wall prescribing concerned people not to transfer or sell the property without prior permission from the agency. As per the youngest son of imprisoned Andrabi, the seized house was the only tangible memory, he had about his incarcerated parents, which was also snatched from him by Indian agencies. In an interview with Kashmir Lit 20-year-old, Ahmad Qasim talks about the longingness, memory and harsh realities of growing up in a densely militarized state of Jammu and Kashmir.

UB: Your father has spent 26 years in prison. Your mother has also faced imprisonment repeatedly, she continues to remain behind bars since 2014 during these years what problems have you faced it must have been tough?

AQ: I have no memory of my father outside prison. I was born in 1999 and he was detained two months after my birth. Until I was 6, I was told that my father was in jail for not doing his homework, my own mother’s real name was kept from me, fearing harassment and interrogation in school. I grew up in hideouts. I used to constantly wonder why my father chose imprisonment over a life with his family, over playing with his son. The idea of home was always missing. I saw my father’s torture scars once. We were in a meeting room. I was terrified. But he smiled while he showed them to me. Even today when I feel timid, it helps me have courage.

I always waited for the day when I had to meet my father. The first half of that day was the best for me. I used to dress up nice, just like Eid. But the heavy frisking by the Indian army men always infuriated me. It felt as if they are more entitled to him than I am.

After losing a father to prison, my whole childhood was consumed by praying for the mother’s safety. She was all I and my brother had. But now she’s imprisoned too. I remember when the police came to arrest her, I just closed my eyes after hugging her one final time. I did not want to see what was happening. I hated being helpless, about my own mother. I wait for her monthly phone calls now. These two-minutes mean more to me than I can tell.

UB: How do you respond to the repeated crackdown at the hands of the state authorities?

AQ: National Investigation Agency raided our home thrice in the middle of the night found no evidence to substantiate their so-called terror collective. Yet, after jailing my parents and driving us out of our home, now they have seized the house too. We can’t enter it anymore. We had moved to the house in 2006, because our father expected that he’d be released in 2008, having finished his 14 years in jail. But that never happened. Harassment by the Indian authorities is normal for us. We would be worried if they liked us.

Since the growth of far-rightwing Hindu nationalism in India, this harassment has only increased. My father Ashiq Faktoo was in Central Jail, Srinagar. He was moved to Udhampur and kept in the barrack of drug-addicts, rapists and thieves.

I remember when I was a child I wanted my father who was imprisoned to accompany me to my school on parent-teacher meetings. So, I got very angry I went to meet him in jail and told him, ‘Why can’t I have a normal life’? He smiled held my hand and told me that our life was as normal as it could get. I could not fathom how, back then. Later when I read George Orwell’s 1984, this statement in the book struck me: ‘The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better.’ For my parents and the majority of Kashmiris, happiness at the cost of freedom feels preposterous. We refuse to be happy until we are free.

UB: What do you mean when you say you are half orphan of Kashmir?

AQ: Half-orphan is how countless children in Kashmir feel. Despite having a father alive, you still feel a void. In case of being half-orphan either one’s father is facing years of imprisonment (for speaking the truth) or he is subjected to enforced disappearance.

As a child, I don’t understand the meaning of it. The conflict stirs a war within me and I always hoped against hope. I was believing, someday my father and my mother will come back from prison. I used to wait for the next hearing in the court, until every festival. I would hope. But the novelty of hope dies each time. So, you wonder if you should accept what is. But it’s hard. Just like half-widows, it’s even harder for children. These children stop expecting justice, and that is very inimical to their growth.

UB: You’ve written extensively about your experience on social media you’ve often claimed your posts are blocked why is that happening to you?

AQ: Indian government, abetted by their media, uses disinformation and propaganda to subvert our legitimate political struggle. The incessant internet blockades, jails full of political prisoners, journalists detained for covering stories of our sufferings – these are the telltale signs of how India fears truth. The NIA summoned a Kashmir-based journalist, Aquib Javaid for interviewing my mother. I am her son. I have witnessed injustice and oppression every day of my life, for 19 years now. I have studied it more from my own life than from books. It has become necessary for Kashmiris to tell their stories themselves.

When I narrate my personal history and experience on social media or media, it is difficult for the Indian government to disparage it. It’s a living fact. So, they block my accounts or posts.

I created a Twitter account and soon after it gained followers, India withheld it, due to a post where I had asked former chief minister Mehbooba Mufti to not pretend to defend human rights of Kashmiri political prisoners. She jailed my mother and curbed visitations. I am continuing to write because I don’t believe in suffering silently. Living in Kashmir, an unexpressed truth is as sinister as a lie. It helps the oppressor.

UB: What are the obstacles in terms of seeking justice in Kashmir especially in case of political prisoners what’s your impression?

AQ: I wanted to be a lawyer when I was a kid. I wanted to fight my father’s case and get him out. But there is no justice when the legal system is at the helm of an occupation that is criminal. There are endless representative cases for this. From the hanging of Afzal Guru to the extrajudicial killing of Rizwan Asad. India operates in Kashmir with complete impunity. My father was detained in 1993. He was subjected to third-degree torture and a confessional statement was drawn out of him under duress, while he was hung upside down and bleeding due to electrocution. He was kept in prison until 1999 and in July of 2001, my father was acquitted of the murder charges by an Indian court, under the following observation: “The prosecution has miserably failed to prove the case against the accused persons.”

The government challenged the acquittal in the Supreme Court of India, despite no presence of evidence or a witness, the acquittal was overturned in January 2003 and his detention was prolonged to 14 years, then to 20 years and finally to death. In the case of political prisoners, Indian courts have miserably failed to deliver justice. They have only helped the government buy time, our time with our families. The obstacle in the path of justice is State itself. After 26 years of his unlawful imprisonment, there is no court in this world that I can seek justice from. There is no law that compels India to return my imprisoned parents.

UB: Have you visited your parents in prison in these months how are the condition of political prisoners languishing in different jails in India?

AQ: Yes, my father is in Udhampur Jail and my mother is in Tihar. When my father was first arrested, the prison cell he and other inmates were kept in had no windows but just a small passage for ventilation. It is designed in this way, to keep one constantly disoriented. He told me that the passage of time was bewildering, and it was impossible to know even if it was night or day. The only sound he could discern was that of his heartbeat. He was tortured. My mother was forced to see everything. He was stripped, and his nails were uprooted. Salt and spices were applied to his wounds. He was electrocuted. There was no respite. At night, they used to release mice in his cells. He is suffering from Glaucoma and his eyesight is deteriorating with every passing day. He is supposed to be examined by an ophthalmologist at regular intervals. The directions have been issued by the High Court, but they have ignored the court orders. He is also a patient of chronic disk problem documented by MRI, but treatment is denied to him.

My mother is kept in a similar cell. The food is served in polythene bags. She suffers from arthritis and asthma, but they don’t even take her to hospital. The doctors in police hospitals declare the patient healthy without even checking them. I witnessed it myself when my mother was jailed in Central Jail, Srinagar. The Indian government is quick to allude to the Geneva Convention when it is convenient for them, but it violates every single humanitarian law in the case of our prisoners.

Umer Beigh is a journalist from Indian-administered Kashmir. He is a graduate of the Nelson Mandela Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution at Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi.